| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.gastrores.org |

Original Article

Volume 11, Number 2, April 2018, pages 130-137

Direct-Acting Antivirals in Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype 4 Infection in Community Care Setting

Vijay Gayama, c, Mazin Khalida, Amrendra Kumar Mandala, Muhammad Rajib Hussaina, Osama Mukhtara, Arshpal Gilla, Pavani Garlapatia, Binav Shresthaa, Debra Gussb, Jagannath Sherigarb, Mohammed Mansoura, Smruti Mohantyb

aDepartment of Medicine and Gastroenterology, Interfaith Medical Center, 1545 Atlantic Ave., Brooklyn, NY 11213, USA

bDepartment of Medicine and Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, 506 6th St., Brooklyn, NY 11215, USA

cCorresponding Author: Vijay Gayam, Interfaith Medical Center, 1545 Atlantic Ave., Brooklyn, New York, 11213, USA

Manuscript submitted March 6, 2018, accepted March 23, 2018

Short title: DAAs in Chronic HCV GT-4 in Community Setting

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr999w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Limited data exists comparing the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 4 (HCV GT-4) in the community practice setting. We aim to evaluate the treatment response of DAAs in these patients.

Methods: All the HCV GT-4 patients treated with DAAs between January 2014 and October 2017 in a community clinic setting were retrospectively analyzed. Pretreatment baseline patient characteristics, treatment efficacy with sustained virologic response (SVR) at 12 weeks post treatment (SVR12), and adverse reactions were assessed.

Results: Fifty-two patients of Middle Eastern (primarily Egyptian) descent were included in the study. Thirty-two patients were treated with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (Harvoni®) ± ribavirin, 12 patients were treated with ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir (ViekiraPak®) ± ribavirin, and eight patients were treated with sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir (Epclusa®). Ten patients (19.2%) had compensated cirrhosis. Overall, SVR at 12 weeks was achieved in 94% in patients who received one of the three DAA regimens (93.8% in Harvoni® group, 91.7 % in ViekiraPak® group and 100% in Epclusa® group). Prior treatment status and type of regimen used in the presence of compensated cirrhosis had no statistical significance on overall SVR achievement (P value = 0.442 and P value = 0.091, respectively). The most common adverse effect was fatigue (27%).

Conclusions: In the real-world setting, DAAs are effective and well tolerated in patients with chronic HCV GT-4 infection with a high overall SVR rate of 94%. Large-scale studies are needed to further assess this SVR in these groups.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis C genotype 4; Direct-acting antiviral agents; Sustained virologic response; Adverse drug reactions

| Introduction | ▴Top |

There are estimated 71 million people infected with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide, and approximately 399,000 people die each year from hepatitis C [1, 2]. Chronic HCV infection is a common cause of chronic progressive liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma [3, 4]. In the United States, it is estimated that 2.7 million people are chronically infected with HCV infection [4, 5].

HCV genotype 4 (HCV GT-4) is responsible for about 13% of all HCV infections worldwide and only 1-2% in the United States [6]. It is common in the Middle East, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa and accounts for more than 90% of all HCV infections in Egypt.

Due to unequal geographic distribution and non-dominant hepatitis C genotype, the representation of HCV GT-4 in clinical trials and other studies is sparse. Thus, the efficacy and safety data of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) in patients with HCV GT-4 infection are limited [5]. Most of the clinical trials and studies that evaluated the effect of DAAs were done on patients with hepatitis C genotype 1(HCV GT1), and many of the findings were generalized to all genotypes. HCV GT-4 patients have limited representation in all the existing literature. In our community, HCV genotype 4 also seems prevalent besides genotype 1 probably due to Egyptian community coming for the treatment. We sought to 1) characterize the population characteristics for HCV GT-4 infection receiving DAAs; 2) evaluate the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of second-generation DAA-based three different combination regimens and assess the indicators that impact sustained virologic response (SVR) rates.

| Patients and Methods | ▴Top |

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the patients were recruited from two specialty clinics attached to the two large community hospitals: Interfaith Medical Center and New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital.

Patients

A total of 61 patients with chronic HCV genotype 4 were treated with DAAs between January 2014 and October 2017. Nine patients were excluded from the study for various reasons including insufficient documentation of viral load during the treatment and failure to follow-up at the end of treatment. Decompensated cirrhosis and HIV co-infection were also excluded from the study. None of the patients included in this study discontinued the treatment due to adverse events associated with treatment medications.

The 52 remaining patients included in this retrospective cohort study received at least 12 weeks of treatment with one of the recommended combination regimens in standard doses for chronic HCV infection. Three different treatment regimens were used in our study. The choice of treatment regimens used was made on the basis of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Ledipasvir 90 mg/day + sofosbuvir 400 mg/day (Harvoni®), ledipasvir 90 mg/day + Sofosbuvir 400 mg/day + ribavirin 1,000 mg/day if < 75 kg and 1,200 mg/day if ≥ 75 kg (Harvoni® + RBV), (ombitasvir 12.5 mg + paritaprevir 75 mg + ritonavir 50 mg) two tablets twice daily + dasabuvir 250 mg twice daily (Viekira Pak®), ombitasvir 12.5 mg + paritaprevir 75 mg + ritonavir 50 mg two tablets twice daily plus dasabuvir 250 mg twice daily + ribavirin 1,000 mg/day if < 75 kg and 1,200 mg/day if ≥ 75 kg (Viekira Pak® + RBV), and sofosbuvir 400 mg/day + velpatasvir 400 mg/day (Epclusa®). Duration of the treatment period ranged from 12 weeks (n = 44) to 24 weeks (n = 8) depending on their status of prior treatment and cirrhosis.

Study assessments

Pretreatment baseline characteristics (Table 1), laboratory studies, baseline HCV viral load, treatment efficacy with SVR at 12 weeks after completion of treatment (SVR 12) were assessed. The safety and tolerability of antiviral drug regimens were assessed by reviewing the documented common or serious adverse events, treatment completion rate, and reduction in the medication dosage or discontinuation of medications.

Click to view | Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients at Baseline with Treatment Regimen |

Liver fibrosis assessment was performed with invasive liver biopsy in some cases and noninvasive testing with a fibro sure test and the aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-aspartate platelet ratio index (APRI) score. Patients who had clinical, laboratory, and radiological evidence of cirrhosis were treated without any further assessment of fibrosis. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on clinical symptoms, laboratory parameters including FibroSURE score ≥ 0.75, imaging modalities (Ultrasonography and Computed Tomography Scan) and histopathology whenever indicated. Compensated cirrhosis was defined as the absence of ascites, jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy and variceal bleeding as defined by American Association for the Study of Liver Disease.

Treatment response was assessed with HCV RNA viral load (IU/ mL) at 4 weeks after initiation of treatment, at the end of treatment, and 12 weeks after completion of treatment. The test was performed using COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HCV Quantitative Test, v2.0 (Roche molecular diagnostics) with the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of HCV RNA 15 IU/mL. SVR 12 was defined as the undetectable viral load at 12 weeks after the end of treatment.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS® statistics software package (IBM SPSS® statistics version 21, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Values were expressed as mean ± SD, and mean quantitative values were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Differences in qualitative values were analyzed by Chi-square test. All P values were two-tailed and P value < 0.05 was considered significant. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether there were differences among the group means. Univariate was used for assessing factors related to SVR12. Multivariable logistic regression was performed only in variables with a P value < 0.05 in univariate analysis.

| Results | ▴Top |

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age of the patients in the study of the cohort was 52 years with ranging from 19 to 79 years. Majority of the patients were males 39 (75%) and treatment-naive (82.7%). Ten patients (19.2%) had compensated cirrhosis and nine patients (17.3%) had HCV/HIV co-infection. Nine patients (17.30%) had received prior treatment. Fifteen patients (28.8%) had a history of diabetes; three patients (5.76%) had kidney disease. However, none of the patients had hepatocellular carcinoma, prior liver transplant or decompensated cirrhosis. There was no statistical difference in the baseline of the three treatment groups except for the Epclusa® group (higher number of cirrhotics and low platelet count).

Treatment regimens

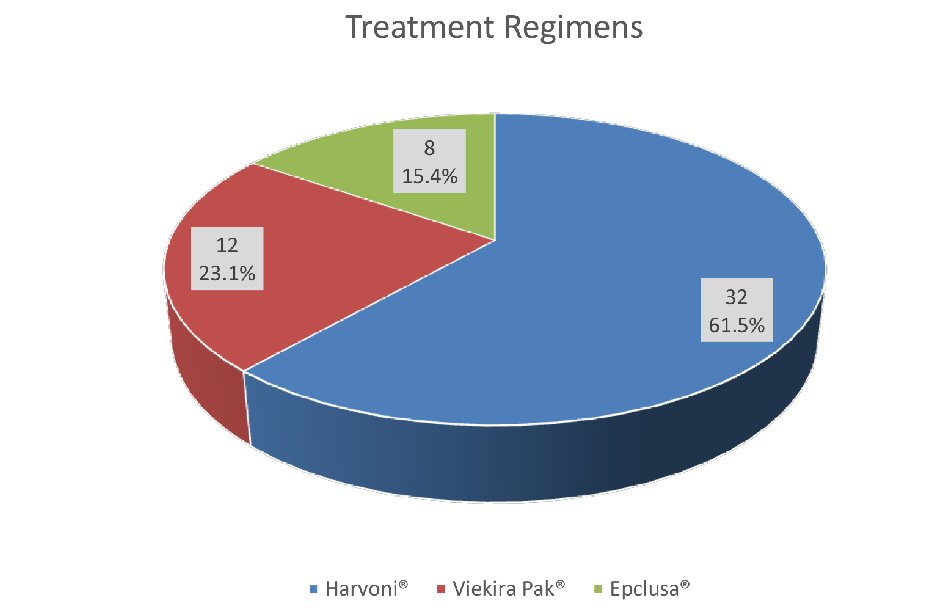

Among the 52 patients with chronic HCV genotype 4 (HCV GT-4) infection, 32 patients (61.53%) were in ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (Harvoni®) group, 12(23.07%) in ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir (Viekira Pak®) group and 8 patients (15.38%) patients in sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa®) group (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Treatment groups with different regimens. |

Overall virologic response to treatment and predictors

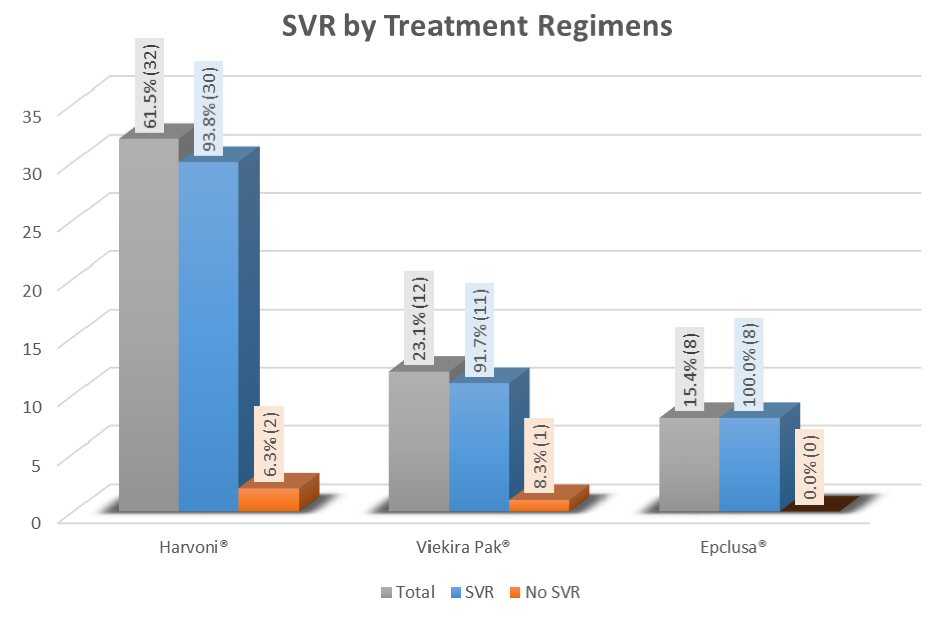

The overall SVR on completion of treatment was 94.23%. SVR 12 in three treatment groups is depicted in Figure 2. In univariate analysis, it was identified that patients who achieved SVR12 as compared to those who did not achieve SVR12 had higher mean albumin value and lower mean bilirubin level (4.2 vs. 3.6; P value = 0.039 and 0.5 vs. 1.0, P value = 0.048, respectively). However, after adjusting baseline characteristics in multivariable logistic regression models, neither albumin nor bilirubin was identified as a predictor of treatment response (P value = 0.99 in both cases). SVR was not affected by HCV RNA levels and previous treatment (Table 2). Overall SVR 12 rates were high and similar in all treatment groups.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Treatment response in all groups measured by overall SVR 12. |

Click to view | Table 2. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients at Baseline by Treatment Response |

Virologic response in Harvoni® group

In this group, 93.8% achieved SVR. In univariate analysis, patients without cirrhosis had higher SVR rates compared to those with cirrhosis (100% vs. 50%, P value = 0.012). But this finding was not confirmed in multivariate analysis after adjusting for baseline characteristics (P value = 0.996). In general, other co-morbidities including diabetes, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, chronic anemia, etc. did not impact SVR rates significantly (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. SVR 12 Rates in Patients Receiving Harvoni® by Population Subgroup |

Virologic response in Veikira Pak® group

Patients treated in this group (ViekiraPak®), 91.7% achieved SVR as shown in Table 4. Similar to Harvoni® group, there was no difference in SVR between cirrhosis and non-cirrhosis patients (100% vs. 90.9%, P value = 1.0).

Click to view | Table 4. SVR 12 Rates in Patients Receiving Viekira Pak® by Population Subgroup |

Virologic response in Epclusa® group

In this treatment group, eight (100%) achieved SVR (Table 5). This finding is encouraging but may not be truly significant due to minimal sample size. Further studies are required to confirm the real significance of these findings.

Click to view | Table 5. SVR 12 Rates in Patients Receiving Epclusa® by Population Subgroup |

Safety

Out of 52 patients in this study, none of the patients discontinued DAA therapy because of an adverse event. A complete list of all adverse events is shown in Table 6. Fatigue, anemia, arthralgia, nausea, and leucopenia were the most common adverse events observed. There were not any serious adverse events seen among those on all regimens. None of the adverse events were statistically significant among three groups except for anemia which was significantly observed in Viekira Pak® group.

Click to view | Table 6. Treatment Adverse Events |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This study represents the data regarding the efficacy of HCV GT4 treatment in a diverse group of patients including both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients, and those with and without several co-morbidities including cirrhosis. We compared treatment efficacy and tolerability with the existing literature in HCV GT-4 patients. In this community-based hospital retrospective study of HCV-GT4, we observed high SVR rates in all the treatment groups.

The SVR achieved in a study by El-Zayadi et al with interferon-based regimens in HCV-GT4 was between 66% to 69%, moreover the duration of treatment was even longer ranging from 24 to 48 weeks [7]. Lawitz et al showed that with the addition of DAA, especially sofosbuvir plus peginterferon and ribavirin in the open-label study for 12 weeks of treatment in a single group achieved high efficacy in treatment naive patients [8].

Subsequently, Ruane et al reported that sofosbuvir and ribavirin alone for 12 to 24 weeks had a wide variation in SVR rates ranging between 59% and 100% in both HCV GT4 treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients [9]. Another multicenter trial (PEARL-I RCT) had also shown that 12-week regimen of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ ritonavir ± ribavirin had high SVR12 in HCV GT 4 patients [10]. This study is also comparable to our study, where patients receiving the same regimen demonstrated equal efficacy regarding SVR in all the subjects in that group.

Unlike other trial, with peginterferon, our study with DAA based regimens had no impact on the pretreatment HCV RNA levels [11]. Treatment among cirrhotics also did not have an impact on SVR 12 in all the regimens.

In our study, among subjects who received SOF/LDV, the overall SVR rate was as high as 93.8 %. This was similar to a study conducted by Hassanein et al where treatment with SOF/LDV for 12 weeks was evaluated in 21 treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients [12]. This study showed that 19 of 20 (95%) achieved SVR12 which was similar to our study. In another trial (the SYNERGY trial), the overall SVR in SOF/LDV for 12 weeks was well tolerated and SVR achieved was 100% regardless of previous treatment status and underlying liver cirrhosis [13]. However, SVR 12 achieved in compensated cirrhosis was only 50% in our study, which could be attributed to small sample size with cirrhosis. El-Khayat et al in a recent real world study done on adolescents with HCV GT4 with SOF/LDV regimen also showed SVR 12 of 99 % [14]. Our study was also similar to another clinical trial by Feld et al in terms of SVR 12 with similar regimens regardless of cirrhosis and treatment-experienced status [15].

Currently, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir is a pan-genotypic HCV treatment option approved for 12 weeks with compensated cirrhosis, which has SVR rates of 99% in all HCV genotypes infection [13-16]. This holds true with our sofosbuvir/velpatasvir group where SVR rate was 100 % and none of the co-morbidities had affected the SVR in any subgroups in this treatment group.

Adverse events seen in our study are consistent with other DAA based studies [8, 17]. None of the patients discontinued therapy due to any adverse effect in any group. This shows that patients tolerate DAA-based regimens quite well in our study. However, anemia was more frequently noted in Viekira Pak® with RBV group as these regimens include ribavirin which is well-known to cause hemolytic anemia.

Our study is unique in assessing and comparing the real-world effectiveness, tolerability, and safety of different therapeutic regimens in HCV GT-4 infection. There are several limitations of our study including retrospective analysis, and a small number of patients were examined, and only subjects with compensated cirrhosis were included.

Conclusions

In the real-world community practice setting, DAAs are effective and well tolerated in patients with chronic HCV GT-4 infection with a high overall SVR rate of 94%. Further large-scale studies are needed to assess response in these groups.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Mohanty is on the Speakers Bureau for Gilead Science, BMS, and Abbvie Pharmaceuticals. For the remaining authors, there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Abbreviations

HCV: hepatitis C virus; HCC: hepatocellular cancer; DAAs: direct-acting antivirals; GT: genotype; SOF: sofosbuvir; RBV: ribavirin; Harvoni®: ledipasvir/sofosbuvir; ViekiraPak®: ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir; SPV: simeprevir; LDV: ledipasvir; Epclusa®: sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; SVR12: sustained virologic response at 12 weeks post treatment; APRI: aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; ESLD: end stage liver disease; ART: antiretroviral therapy

| References | ▴Top |

- Petruzziello A, Marigliano S, Loquercio G, Cozzolino A, Cacciapuoti C. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: An up-date of the distribution and circulation of hepatitis C virus genotypes. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(34):7824-7840.

doi pubmed - WHO:HCV (updated october 2017). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/.

- Abdel-Hamid M, El-Daly M, Molnegren V, El-Kafrawy S, Abdel-Latif S, Esmat G, Strickland GT, et al. Genetic diversity in hepatitis C virus in Egypt and possible association with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 5):1526-1531.

doi pubmed - Freeman AJ, Dore GJ, Law MG, Thorpe M, Von Overbeck J, Lloyd AR, Marinos G, et al. Estimating progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2001;34(4 Pt 1):809-816.

doi pubmed - Smith DB, Bukh J, Kuiken C, Muerhoff AS, Rice CM, Stapleton JT, Simmonds P. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):318-327.

doi pubmed - Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, Razavi-Shearer K, Razavi H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 Suppl):S45-57.

doi pubmed - El-Zayadi AR, Attia M, Barakat EM, Badran HM, Hamdy H, El-Tawil A, El-Nakeeb A, et al. Response of hepatitis C genotype-4 naive patients to 24 weeks of Peg-interferon-alpha2b/ribavirin or induction-dose interferon-alpha2b/ribavirin/amantadine: a non-randomized controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2447-2452.

doi pubmed - Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, Rodriguez-Torres M, Hassanein T, Gordon SC, Schultz M, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878-1887.

doi pubmed - Ruane PJ, Ain D, Stryker R, Meshrekey R, Soliman M, Wolfe PR, Riad J, et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic genotype 4 hepatitis C virus infection in patients of Egyptian ancestry. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1040-1046.

doi pubmed - Hezode C, Asselah T, Reddy KR, Hassanein T, Berenguer M, Fleischer-Stepniewska K, Marcellin P, et al. Ombitasvir plus paritaprevir plus ritonavir with or without ribavirin in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C virus infection (PEARL-I): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2502-2509.

doi - Derbala M, Amer A, Bener A, Lopez AC, Omar M, El Ghannam M. Pegylated interferon-alpha 2b-ribavirin combination in Egyptian patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12(4):380-385.

doi pubmed - Hassanein T, Sims KD, Bennett M, Gitlin N, Lawitz E, Nguyen T, Webster L, et al. A randomized trial of daclatasvir in combination with asunaprevir and beclabuvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection. J Hepatol. 2015;62(5):1204-1206.

doi pubmed - Kohli A, Kapoor R, Sims Z, Nelson A, Sidharthan S, Lam B, Silk R, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 4: a proof-of-concept, single-centre, open-label phase 2a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(9):1049-1054.

doi - El-Khayat HR, Kamal EM, El-Sayed MH, El-Shabrawi M, Ayoub H, Riz KA, Maher M, et al. The effectiveness and safety of ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir in adolescents with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection: a real-world experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(6):838-844.

doi pubmed - Feld JJ, Jacobson IM, Hezode C, Asselah T, Ruane PJ, Gruener N, Abergel A, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(27):2599-2607.

doi pubmed - Foster GR, Afdhal N, Roberts SK, Brau N, Gane EJ, Pianko S, Lawitz E, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(27):2608-2617.

doi pubmed - European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2016. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):153-194.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.