| Gastroenterology Research, ISSN 1918-2805 print, 1918-2813 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Gastroenterol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.gastrores.org |

Original Article

Volume 14, Number 6, December 2021, pages 313-323

Ethnic Minorities and Low Socioeconomic Status Patients With Chronic Liver Disease Are at Greatest Risk of Being Uninsured

Kabiru Ohikerea, Amit S. Chitnisb, Thomas A. Hahambisc, Ashwani Singald, e, Robert J. Wongf, g, h

aDivision of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA, USA

bTuberculosis Section, Division of Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Alameda County Public Health Department, San Leandro, CA, USA

cGilead Sciences Inc., Foster City, CA, USA

dDepartment of Medicine, University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine, Sioux Falls, SD, USA

eDivision of Transplant Hepatology, Avera Transplant Institute, Sioux Falls, SD, USA

fDivision of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

gDivision of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Healthcare System, Palo Alto, CA, USA

hCorresponding Author: Robert J. Wong, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, Stanford University School of Medicine, 3801 Miranda Ave., Palo Alto, CA 94304, USA

Manuscript submitted June 21, 2021, accepted July 15, 2021, published online December 21, 2021

Short title: HAV and HBV Vaccination in CLD Patients

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/gr1439

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Chronic liver disease (CLD) predominantly affects ethnic minorities and socially vulnerable populations, who have high prevalence of risk factors (e.g., suboptimal insurance coverage) predisposing to healthcare disparities. We evaluate prevalence and predictors of uninsured status among CLD adults, and secondarily, how this affects documented immunity or vaccination for hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV).

Methods: Using 2011 - 2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, self-reported insurance status was determined among adults with CLD. Prevalence of uninsured status was stratified by patient characteristics and evaluated using multivariable logistic regression models. Prevalence of self-reported completion of vaccination as well as laboratory value-based documented immunity to HAV and HBV was stratified by insurance status.

Results: Overall, 19.0% of adults with CLD reported having no insurance, which was highest among individuals of Hispanic ethnicity (33.5%), less than high school education (33.7%), and below poverty status (35.3%). On multivariable analyses, significantly lower odds of having any insurance coverage was observed in men, Hispanics, and individuals with lower education and lower household income. Prevalence of documented immunity or vaccination for HAV was low across all insurance categories, ranging from 46.5% to 54.0%. Prevalence of documented immunity or vaccination for HBV was similarly low across all insurance categories, ranging from 24.3% to 40.8%.

Conclusion: Prevalence of uninsured status among CLD was more than twice the US adult population, and lack of insurance particularly impacted Hispanics and individuals with low education and low household income. Low prevalence of documented immunity or vaccination for HAV and HBV across all insurance categories is concerning.

Keywords: Chronic liver disease; Insurance; Vaccination; Hepatitis B; Hepatitis A

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Chronic liver disease (CLD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States of America (USA). Patients with CLD are particularly vulnerable to acute viral hepatitis that may exacerbate underlying liver disease, leading to more aggressive disease progression or an acute flare of underlying liver disease [1-4]. The importance of screening for hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) and subsequent documentation of immunity or initiation of vaccination among patients with CLD in particular is supported by national societies and guideline recommendations [5, 6]. However, existing studies have demonstrated that vaccination for HAV and HBV among patients with CLD remains suboptimal [5, 7-10]. This is a particularly important public health concern given that HAV and HBV are vaccine preventable diseases, whereby timely screening, vaccination, and linkage to care, particularly among individuals with underlying CLD, can significantly improve patient outcomes.

Existing studies have also demonstrated treatment disparities in the management of CLD patients, with Medicaid or uninsured safety-net patients experiencing the lowest rates of treatment and care [11-13]. This is particularly important given that CLD patients are predominantly ethnic minorities and vulnerable individuals of low socioeconomic status (SES) who are primarily insured by Medicaid or safety-net health plans. The high prevalence of CLD patients who are ethnic minorities and who have low SES creates challenges for healthcare systems to provide effective care to these patients. In particular, these CLD patients have a high prevalence of comorbidities such as alcohol and substance use disorders that require consistent care, including regular follow-up in clinics, monitoring of laboratory tests, and vaccination for HAV and HBV [14-16]. In this paper, we evaluate CLD prevalence and rates of documented immunity or vaccination to HAV and HBV by insurance status among US adults.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

We analyzed data from the 2011 - 2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). NHANES incorporates a complex, four-stage clustered sampling design to select a nationally representative sample of the civilian non-institutionalized resident population of the USA in 2-year cycles to examine the health status of residents. NHANES collects data on demographics, general health, and nutrition via in-home questionnaires or interviews. Standardized health examinations are conducted at mobile examination centers to collect information on physical measurements and blood specimens for laboratory testing. NHANES was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics institutional review board and written consent was obtained from participants. Given the inherent limitations of the complex survey design used by the NHANES (i.e., oversampling of certain populations, survey nonresponse, and poststratification), the NHANES provides weighting variables to help account for some of the biases introduced by this complex survey design. Thus, weighting of the data improves the accuracy that calculated estimates are truly representative of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population.

Our study focused on adults with the four most common causes of CLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), alcoholic liver disease (ALD), chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV), and chronic HBV. NAFLD was identified using previously validated algorithms that included presence of both elevated alanine aminotransferase (> 25 U/L in women, > 35 U/L in men) and metabolic syndrome, after excluding other potential causes of CLD [17-19]. ALD was identified using previously published multi-step algorithms that incorporate assessment of alcohol use (> 28 g/day in women and > 42 g/day for men in the past 12 months) and elevated alanine aminotransferase (> 25 U/L in women, > 35 U/L in men), after excluding HCV or HBV [20]. Chronic HBV was identified with hepatitis B surface antigen reactivity and chronic HCV was identified with detectable HCV RNA. The insurance status for each individual was determined based on self-reported insurance coverage and included private/commercial insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, or no insurance. Comparisons of insurance status coverage between individuals with CLD were performed with Chi-square testing. Adjusted multivariate logistic regression models evaluated for predictors of having insurance (vs. no insurance) among individuals with CLD.

Given the importance of ensuring documentation of vaccination for or immunity to HAV and HBV among patients with CLD, our study focused on evaluating prevalence and predictors of documented vaccination for or immunity to HAV and HBV, stratified by insurance status. Prior HAV vaccination was assessed by self-reported receipt of two doses of HAV vaccination, and prior HBV vaccination was assessed by self-reported receipt of three doses of HBV vaccination. Immunity to HAV was determined by presence of HAV total antibody (signal to cutoff ratio < 0.8 using the VITROS Anti-hepatitis A virus Total Reagent Pack/Total Calibrators on the VITROS ECi/ECiQ/360 Immunodiagnostic Systems), and immunity to HBV was determined by HBV surface antibody (anti-HBs >12.0 mIU/mL using the VITROS Anti-HBs Reagent Pack/Calibrators on the VITROS ECi/ECiQ/360 Immunodiagnostic Systems) among patients with no prior exposure to HBV (i.e., hepatitis core antibody total negative).

Prevalence of documented vaccination for or immunity to HAV among individuals with CLD was reported as proportions and frequencies and stratified by insurance status. Similarly, prevalence of documented vaccination for or immunity to HBV among individuals with CLD and no prior HBV exposure (HBV core antibody negative) was analyzed in a similar fashion. Comparisons of documented vaccination for or immunity to HAV and comparisons of documented vaccination for or immunity to HBV between groups were evaluated by Chi-square testing. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA version 14 (StataCorp). Our study adhered to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines. The study was approved by Stanford University Institutional Review Board. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

| Results | ▴Top |

Overall

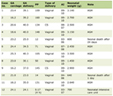

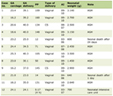

Among US adults with CLD (n = 5,267), 81.0% reported having insurance (58.7% (n = 2,710) private/commercial, 12.6% (n = 737) Medicaid, 9.6% (n = 648) Medicare) and 19.0% (n = 1,172) reported having no insurance (Table 1). Compared to females with CLD, males were more likely to be uninsured (21.2% vs. 16.4%, P < 0.01). Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, significantly higher prevalence of being uninsured was observed among Hispanics (33.5% vs. 13.9%, P < 0.001) and African Americans (22.4% vs. 13.9%, P < 0.001). Non-US born individuals with CLD were also more likely to be uninsured compared to US born individuals (31.9% vs. 16.2%, P < 0.001) (Table 1). Individuals with less than a high school education as well as those whose household income was at or below the poverty level were significantly more likely to be uninsured. With time, the proportion of CLD individuals with no insurance decreased from 23.3% in 2011 - 2012 to 15.6% in 2017 - 2018 (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of the Chronic Liver Disease Cohort by Insurance Status |

Insurance status among individuals with CLD

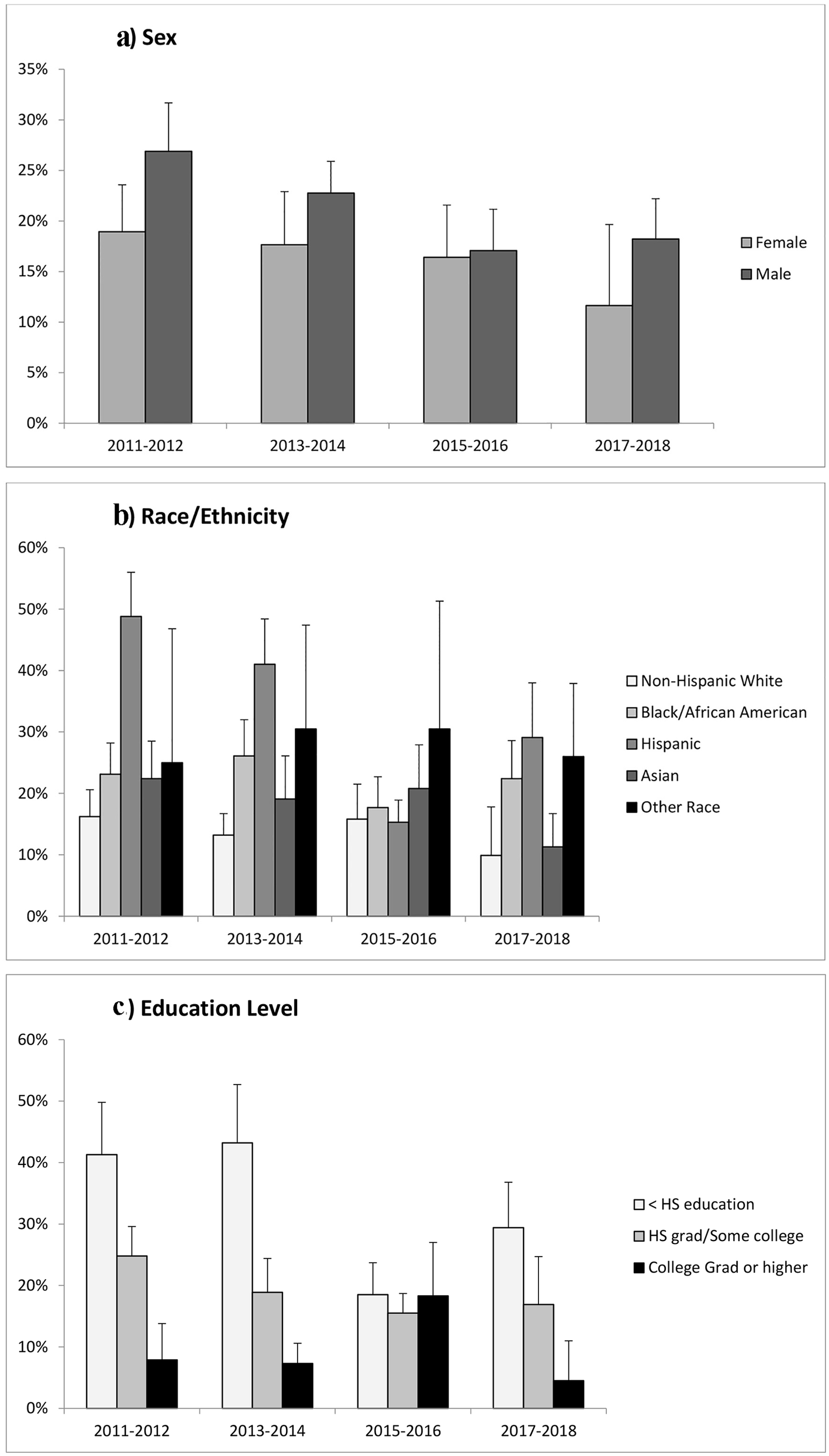

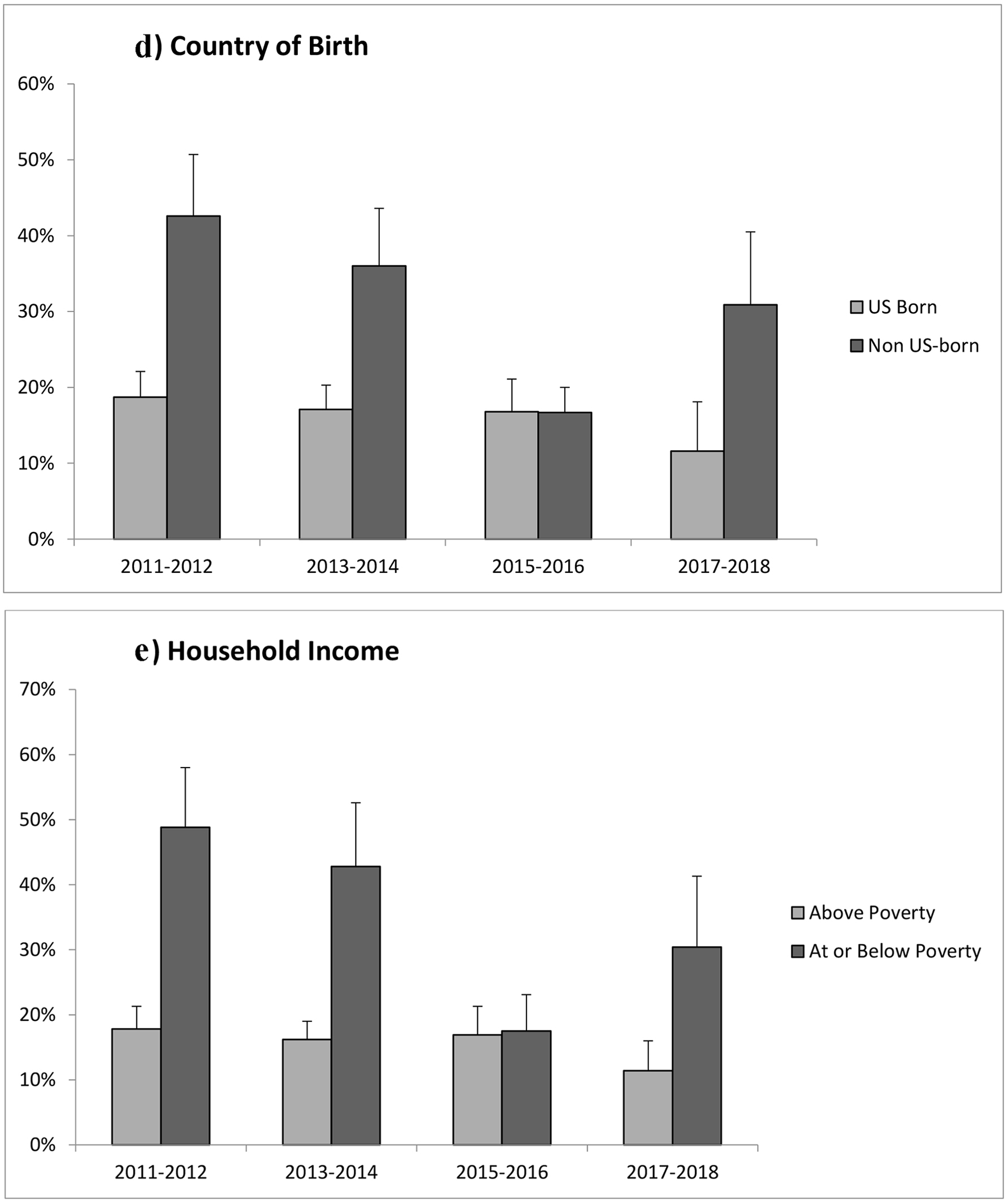

While both males and females with CLD experienced declining prevalence of being uninsured, males with CLD still demonstrated a trend towards higher prevalence of uninsured status compared to females in 2017 - 2018 (18.2% vs. 11.6%, P = 0.14) (Fig. 1). When stratified by race/ethnicity, all race/ethnic groups with the exception of African Americans experienced declining prevalence of uninsured status. In 2017 - 2018, the proportion of CLD individuals reporting no insurance among Hispanics was three times higher than non-Hispanic Whites (29.1% vs. 9.9%, P < 0.01), and the proportion reporting no insurance among African Americans was more than twice that among non-Hispanic Whites (22.4% vs. 9.9%, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Similarly, despite declining prevalence of uninsured CLD patients, in 2017 - 2018, significantly higher prevalence of uninsured status persisted in non-US born vs. US born (30.9% vs. 11.6%, P < 0.01), individuals with less than high school education vs. those with college degree of higher (29.4% vs. 4.5%, P < 0.001), and individuals at or below poverty level vs. those above poverty level (30.5% vs. 11.4%, P < 0.01) (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Proportion of individuals with chronic liver disease who reported being uninsured by (a) sex, (b) race/ethnicity, (c) education level, (d) country of birth, and (e) household income. Note: Error bars represent the upper limit of 95% confidence intervals. |

On multivariate logistic regression among individuals with CLD, males were significantly less likely to have any insurance coverage compared to females (odds ratio (OR) 0.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.63 - 0.90, P < 0.01) (Table 2). Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics were significantly less likely to have insurance coverage (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.52 - 0.86, P < 0.01), and there was a trend towards lower odds of having insurance among African Americans (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.58 - 1.05, P = 0.10). Compared to US born individuals with CLD, non-US born individuals were significantly less likely to have insurance coverage (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.54 - 0.86, P < 0.01) (Table 2). Increasing education level was associated with significantly greater odds of having insurance, and being at or below the poverty level based on household income was associated with significantly lower odds of having insurance coverage (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.47 - 0.69, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Multivariate Logistic Regression Model Evaluating Predictors of Having Insurance vs. No Insurance Among Individuals With Chronic Liver Disease |

HAV vaccination or documented immunity

Overall prevalence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity among adults with CLD was low across insurance status. For example, prevalence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity was 58.5% among those with no insurance, 50.7% among those with Medicaid, 50.4% among those with Medicare, and 46.5% among those with private/commercial insurance (Table 3). When stratified by sex, prevalence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity was similar across insurance status. When stratified by race/ethnicity, prevalence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity was highest among Asians and Hispanics and lowest among non-Hispanic Whites, which was similar across insurance status. Non-US born individuals also had significantly greater prevalence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity compared to US born individuals. When evaluating CLD patients with concurrent metabolic disorders, such as diabetes or metabolic syndrome, alarmingly only about half of these patients had evidence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity (Table 3). While 84.8% of uninsured CLD with advanced fibrosis had evidence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity, among CLD individuals with advanced fibrosis covered by private/commercial, Medicare, or Medicaid insurance, less than 40% had evidence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity (Table 3). Interestingly, those with lower education level and lower household income had higher prevalence of HAV vaccination or documented immunity across different insurance types.

Click to view | Table 3. Proportion of Individuals With Chronic Liver Disease With Self-Reported Vaccination or Documented Immunity to Hepatitis A Virus |

HBV vaccination or documented immunity

Overall prevalence of HBV vaccination or documented immunity among adults with CLD and no prior HBV exposure was suboptimal across insurance status (40.8% among those with no insurance, 39.6% among those with Medicaid, 24.3% among those with Medicare, and 39.6% among those with private/commercial insurance) (Table 4). When stratified by sex, females with CLD generally had higher prevalence of HBV vaccination or documented immunity compared to males, with the exception of individuals with Medicare where HBV vaccination or documented immunity was poor among males and females. Among race/ethnic groups, Asians had the highest prevalence of HBV vaccination or documented immunity, whereas prevalence among non-Hispanic Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics was similar across insurance types. Among CLD individuals with no insurance, US born individuals had higher prevalence of HBV vaccination or documented immunity compared to non-US born (46.1% vs. 28.3%, P < 0.01), but no differences between US born and non-US born were observed across other insurance categories (Table 4). Among CLD individuals with concurrent metabolic disorders, such as diabetes or metabolic syndrome, alarmingly only about a third of those with private/commercial insurance, Medicaid, or no insurance had evidence of HBV vaccination or documented immunity, and only about 20% of those with Medicare had evidence of HBV vaccination or documented immunity (Table 4). Among CLD patients with advanced fibrosis, evidence of HBV vaccination or documented immunity was observed in 68.5% of those with no insurance, 49.8% of those with private/commercial insurance, 27.5% of those with Medicare, and 42.9% of those with Medicaid. There seemed to be a trend towards higher prevalence of HBV vaccination or documented immunity with higher education level, but no significant difference was observed between individuals at or below poverty vs. those above poverty levels.

Click to view | Table 4. Proportion of Individuals With Chronic Liver Disease and No Prior Hepatitis B Exposure Who Have Self-Reported Vaccination or Documented Immunity to Hepatitis B Virus |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Our current study of US adults with CLD emphasizes the underserved and vulnerable nature of these individuals. Nearly 20% of all CLD patients reported having no insurance, which is more than twice the uninsured prevalence observed in the US adult population [21]. Proportion of CLD patients reporting no insurance was even greater among ethnic minorities, immigrants, and those with lower SES as measured by education and income status. This is particularly important given the existing literature that demonstrates suboptimal access to high quality liver disease care and treatment among individuals with Medicaid or no insurance, as well as those vulnerable populations that are represented by ethnic minorities, immigrants and those of lower SES. Even more alarming, among these socially vulnerable CLD individuals, our study reports suboptimal protection against HAV and HBV, which are vaccine preventable diseases that carry high risk of morbidity and mortality particularly in patients with CLD. It is also important to interpret these observations in the context of the US healthcare system. Unlike other countries or world regions that have a single payer universal coverage policy, there are several options in the USA for healthcare coverage, including employer sponsored health insurance (for individuals who are currently employed or those that retain insurance through their employer’s retirement program), government sponsored health insurance (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid), as well as various forms of indigent care coverage that may be specific to local municipalities (e.g., county health insurance). Individuals who do not qualify for aforementioned options can also purchase heath insurance separately. Among patients with CLD, vaccination coverage for both HAV and HBV is generally covered without difficulty. Thus low rates of HAV and HBV vaccination in the US healthcare system are generally attributed to disparities in access to care or sub-optimal awareness and referral for vaccination from providers.

Disparities in liver disease care among ethnic minorities and underserved populations may be associated with suboptimal insurance status converging with low SES. Furthermore, the observation that a large proportion of CLD patients are underinsured and receive care in safety-net healthcare settings, which is associated with significant disparities and delays in care due to costs as well as negative perceptions and barriers to care, is an important public health concern that deserves greater focus [22]. For example, a study in Vietnamese immigrants observed that suboptimal HBV screening was associated with insurance status, low English fluency, and lower education level [23]. Similar data from Hu et al evaluated 53,896 adults from the 2009 - 2010 Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) cohort across the USA and observed that only 39.2% of individuals received HBV screening [24]. Even more concerning, among those with confirmed chronic HBV, only 33.3% were linked to a HBV provider, with significantly lower rates of testing and linkage to care among individuals who were uninsured or had lower educational level. Similarly, CLD patients receiving care in safety-net settings, which are often under-resourced, have been reported to experience low rates of HBV and HCV treatment [11, 13] as well as higher mortality in patients with cirrhosis or ALD [20, 25]. Suboptimal hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) screening has also been reported for ethnic minorities and underserved populations with liver disease. For example, a study of 904 cirrhosis patients at a single safety-net hospital observed that less than 2% received appropriate HCC screening [26]. In particular, African Americans were 39% less likely to receive HCC screening compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Similar data were observed among US veterans with HCV cirrhosis, with African Americans 40% less likely to receive timely HCC screening [27]. Surrogates of low SES such as unemployment [28], lower household income [29-31], and lower education level [29] are associated with lower rates of HCC screening. Furthermore, data from the US Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database demonstrate that HCC patients with no insurance or Medicaid coverage had more advanced HCC at time of diagnosis, lower rates of HCC treatment, and ultimately lower overall survival. The large proportion of CLD patients who are uninsured in our cohort, particularly among minorities and low SES individuals, is particularly concerning given the existing data showing suboptimal care in these populations.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that adults with CLD have documented immunity or receive appropriate vaccination for HAV and HBV [5, 6]. This primarily stems from the observation that HAV or HBV co-infection in CLD patients is associated with more rapid and progressive liver injury, acute decompensation, and increased risks of death [1-4]. Despite this recommendation, vaccinations rates remain suboptimal [10]. Kramer et al evaluated US adults with chronic HCV and observed that only 21.9% and 20.7% received HAV or HBV vaccination, respectively [7]. Similarly, 57.0% and 45.5% had documented immunity or vaccination for HAV or HBV, respectively. Henkle et al evaluated data from the 2006 - 2008 Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study and observed that over 40% of patients with chronic HBV or chronic HCV do not have documented immunity or vaccination to HAV or HBV [9]. Our study of adults with CLD in the USA further adds to these existing data and demonstrates that across all insurance categories, documented immunity or vaccination to HAV and HBV are suboptimal. Furthermore, even among individuals with concurrent metabolic disorders or advanced fibrosis, rates of documented immunity or vaccination to HAV and HBV remain unacceptably low.

Certain limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. Insurance status in NHANES is self-reported by the individual at the time the NHANES survey was conducted and may have changed since the interview. Vaccination data in NHANES are also self-reported and may be subject to recall bias. However, our study utilized both self-report of vaccination as well as documented immunity by laboratory assessment, which incorporates an objective measurement of immunity. The definition of CLD is based on prior established definitions that use multistep algorithms that include comorbidities, laboratory data, and self-reported alcohol use. Thus some degree of misclassification may have occurred and likely underestimated true disease prevalence.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that adults with CLD represent an underserved and vulnerable group, which includes a large proportion with Medicaid or no insurance, low household income, and low education status. In fact, prevalence of uninsured status among adults with CLD is more than twice that observed among the average US adult population. Even more concerning, rates of documented vaccination or immunity to HAV or HBV were suboptimal across different insurance coverage, and across different high-risk groups including those with low SES as well as significant comorbidities. Our study highlights the need for greater focus and public health initiatives to improve HAV and HBV vaccination among patients with CLD.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Written consent was obtained from participants.

Author Contributions

Dr. Wong had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Ohikere, Chitnis, Wong. Acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and statistical analysis of data: Ohikere, Chitnis, Hahambis, Singal, Wong. Drafting and critical revision of the manuscript: Ohikere, Chitnis, Hahambis, Singal, Wong Administrative, technical, or material support: Wong. Supervision: Wong.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

ALD: alcoholic liver disease; CLD: chronic liver disease; HAV: hepatitis A virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; SES: socioeconomic status

| References | ▴Top |

- Keeffe EB. Acute hepatitis A and B in patients with chronic liver disease: prevention through vaccination. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 10A):21S-27S.

doi pubmed - Koff RS. Risks associated with hepatitis A and hepatitis B in patients with hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(1):20-26.

doi pubmed - Reiss G, Keeffe EB. Review article: hepatitis vaccination in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(7):715-727.

doi pubmed - Vento S, Garofano T, Renzini C, Cainelli F, Casali F, Ghironzi G, Ferraro T, et al. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(5):286-290.

doi pubmed - Nelson NP, Weng MK, Hofmeister MG, Moore KL, Doshani M, Kamili S, Koneru A, et al. Prevention of Hepatitis A Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69(5):1-38.

doi pubmed - Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, Harris A, Haber P, Ward JW, Nelson NP. Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67(1):1-31.

doi pubmed - Kramer JR, Hachem CY, Kanwal F, Mei M, El-Serag HB. Meeting vaccination quality measures for hepatitis A and B virus in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 2011;53(1):42-52.

doi pubmed - Younossi ZM, Stepanova M. Changes in hepatitis A and B vaccination rates in adult patients with chronic liver diseases and diabetes in the U.S. population. Hepatology. 2011;54(4):1167-1178.

doi pubmed - Henkle E, Lu M, Rupp LB, Boscarino JA, Vijayadeva V, Schmidt MA, Gordon SC, et al. Hepatitis A and B immunity and vaccination in chronic hepatitis B and C patients in a large United States cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(4):514-522.

doi pubmed - Wong RJ, Gish RG, Cheung R, Chitnis AS. low prevalence of vaccination or documented immunity to hepatitis A and hepatitis B viruses among individuals with chronic liver disease. Am J Med. 2021;134(7):882-892.

doi pubmed - Wong RJ, Jain MK, Therapondos G, Shiffman ML, Kshirsagar O, Clark C, Thamer M. Race/ethnicity and insurance status disparities in access to direct acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(9):1329-1338.

doi pubmed - Wang J, Ha J, Lopez A, Bhuket T, Liu B, Wong RJ. Medicaid and uninsured hepatocellular carcinoma patients have more advanced tumor stage and are less likely to receive treatment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(5):437-443.

doi pubmed - Wong RJ, Jain MK, Therapondos G, Niu B, Kshirsagar O, Thamer M. Low Rates of Hepatitis B Virus Treatment Among Treatment-Eligible Patients in Safety-Net Health Systems. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021.

doi pubmed - Flemming JA, Saxena V, Shen H, Terrault NA, Rongey C. Facility- and patient-level factors associated with esophageal variceal screening in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(1):62-69.

doi pubmed - Kanwal F. Quality of care assessment in chronic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2014;4(6):149-152.

doi pubmed - Kanwal F, Tapper EB, Ho C, Asrani SK, Ovchinsky N, Poterucha J, Flores A, et al. Development of Quality Measures in Cirrhosis by the Practice Metrics Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69(4):1787-1797.

doi pubmed - Wong RJ, Liu B, Bhuket T. Significant burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis in the US: a cross-sectional analysis of 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(10):974-980.

doi pubmed - Younossi ZM, Otgonsuren M, Venkatesan C, Mishra A. In patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolically abnormal individuals are at a higher risk for mortality while metabolically normal individuals are not. Metabolism. 2013;62(3):352-360.

doi pubmed - Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, Srishord M. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(6):524-530 e521; quiz e560.

doi pubmed - Dang K, Hirode G, Singal AK, Sundaram V, Wong RJ. alcoholic liver disease epidemiology in the United States: a retrospective analysis of 3 US databases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(1):96-104.

doi pubmed - Keisler-Starkey K, Bunch L. U.S. Census Bureau current population reports, health insurance coverage in the United States: 2019. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2020. p. 60-271

- Becker G. Deadly inequality in the health care "safety net": uninsured ethnic minorities' struggle to live with life-threatening illnesses. Med Anthropol Q. 2004;18(2):258-275.

doi pubmed - Choe JH, Taylor VM, Yasui Y, Burke N, Nguyen T, Acorda E, Jackson JC. Health care access and sociodemographic factors associated with hepatitis B testing in Vietnamese American men. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(3):193-201.

doi pubmed - Hu DJ, Xing J, Tohme RA, Liao Y, Pollack H, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. Hepatitis B testing and access to care among racial and ethnic minorities in selected communities across the United States, 2009-2010. Hepatology. 2013;58(3):856-862.

doi pubmed - Wong RJ, Hirode G. The effect of hospital safety-net burden and patient ethnicity on in-hospital mortality among hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(7):624-630.

doi pubmed - Singal AG, Li X, Tiro J, Kandunoori P, Adams-Huet B, Nehra MS, Yopp A. Racial, social, and clinical determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):90 e91-97.

doi pubmed - Davila JA, Henderson L, Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson PA, Duan Z, El-Serag HB. Utilization of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among hepatitis C virus-infected veterans in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):85-93.

doi pubmed - Singal AG, Volk ML, Rakoski MO, Fu S, Su GL, McCurdy H, Marrero JA. Patient involvement in healthcare is associated with higher rates of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(8):727-732.

doi pubmed - Davila JA, Morgan RO, Richardson PA, Du XL, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Use of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2010;52(1):132-141.

doi pubmed - Wong RJ, Saab S, Konyn P, Sundaram V, Khalili M. Rural-urban geographical disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence among US adults, 2004-2017. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(2):401-406.

doi pubmed - Wong RJ, Kim D, Ahmed A, Singal AK. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma from more rural and lower-income households have more advanced tumor stage at diagnosis and significantly higher mortality. Cancer. 2020;127(1):45-55.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Gastroenterology Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.